[:en]

“You’re doing it wrong, Kateri!”

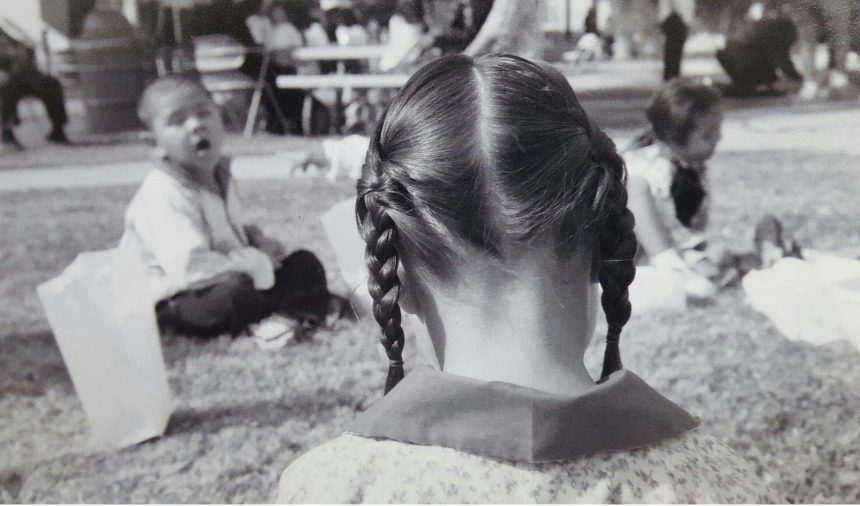

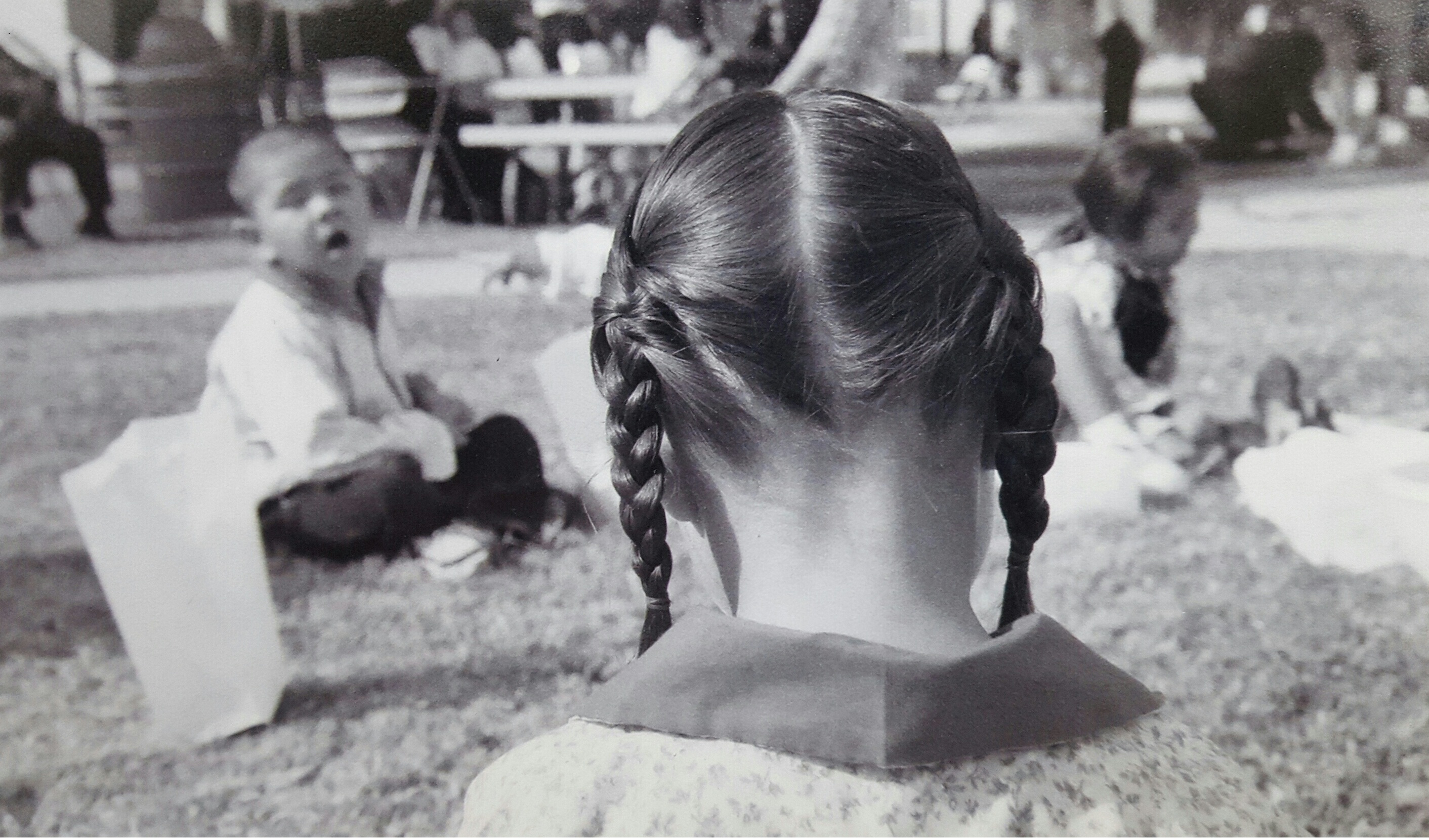

I was 6 years old and my first grade class performed a “traditional” pueblo line dance for our school. “You do it like this,” my critic, a blonde white boy, said as he hopped from foot to foot.

I insisted, “I’m not doing it wrong, I’m an Indian?!”

At the time, I didn’t recognize what a horrible appropriation our little performance was, but I was incensed. I was mad because I wasn’t about to be told by a white person I wasn’t doing a pueblo dance correctly. And, I wouldn’t be told by any boy I didn’t know how to be an Indian girl.

I am the last authority on Native tradition and culture. But, the little I do know has made me feel more connected and protective of the world and people around me. One thing I know for certain is there is something inherently powerful about being an Indigenous woman.

I had a sense of this feeling when I was an indignant little girl. Now that I’m an adult, it has grown in me as a distinct and powerful identity: Indigenous Feminist.

As a teenager, I didn’t embrace my culture as I should have. I abandoned her, I mocked her and I buried her. But, as I became a mother, as I learned loss and the fragility of my own life, I realized I was wasting the precious time I had to learn my languages, my culture, my birthright.

This impulse has become stronger as I’ve begun the process of decolonizing my way of thinking. And as I began realizing the reasons why I tried to downplay my own identity: the self-hate and shame were symptoms of internalized racism. That’s how it works—from inside out.

Although I was not embracing my cultural roots in adolescence, I was busy crafting the feminist ideals I think are necessary for all young girls. I didn’t know it then, but I was preparing myself. I was preparing for a life where I, like all women, was guaranteed violence, misogyny and injustice.

My Armour

I danced—a real dance—for the first time when I was 19. I was worried and ashamed it had taken me so long. I didn’t know the words my clan fathers were singing to me and I lost my rhythm many times. The air was cold, but the weight of my wool manta and layers of jewelry and ribbon made me sweat.

I tried to stay present and listen to the words of the songs I didn’t understand. I tried not to look at my family who was smiling out of pride and humor from my awkward steps. My dance was a blessing for them, a prayer for their health and prosperity.

When I returned home that night, as with every other night, I rushed through my front door and turned on every light making sure no one was waiting in the dark. But, as I felt the soreness gather in my feet and legs and I smelled the earth paint still lingering on my skin, I realized this night, of all nights, I had nothing to fear. I was protected. By the prayers that were sung for me and my family. By the feathers I held to bless myself. I was protected.

Indigenous Feminism is power. But that power is closely followed with, and made possible by, protection. Being Indigenous and feminist protects my heart from the poison of colonization and my mind from the banality and barbarism of patriarchy. And I am grateful for my armour.

During a recent conversation I had with Indigenous environmental activist, Casey Camp Horinek, she said to me, “Prepare, my girl.” She was referring to the work of undoing decolonization and saving our natural mother, but Casey’s words took my breath away. I took them as something much greater and more personal because they embody what I’ve been doing my whole life. I am always preparing.

[:]