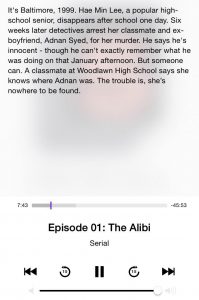

I downloaded Serial, week by week, just like the other five million pairs of ears who were struck by this investigative journalism phenomenon. As a podcast, it blended our favorite parts of a crime drama like True Detective or Breaking Bad, but portable. We were guided through the story of Hae and Adnan by the “relatable” and relentless Sarah Koenig. Koenig is a staff producer at This American Life, and she’s the executive producer and host of Serial. Koenig herself says the show is “about the basics: love and death and justice and truth. All these big, big things.” But that’s what annoys me, how these big, big things distract us from Sarah Koenig’s white privilege, and comfort us with a false sense of justice.

Hae Min Lee is the daughter of Korean immigrants, and Adnan Syed, her accused murderer, comes from a Muslim family. But Serial was never about Hae and Adnan. Instead, Serial is about Sarah Koenig and her confessional-style obsession over the crime.

Koenig is constantly explaining to us how the two of them are such typical teenagers, playing sports, getting grades, falling in love, going to prom… just like anybody else. This serves as context, but the white-washed dream of the U.S. high school experience just shows us Koenig’s trying to make them relatable, like there’s something “other” about them that she can’t quite figure out. She tries to be transparent about this, but it comes off as messy, especially in contrast to how diligently she seems to have researched the case.

There’s no input from Hae’s family during the podcast, which makes her seem so distant from the story of her own death. Adnan, on the other hand, is given lots of air-time to explain himself, and Koenig seems to spend the majority of her time trying to understand the Muslim community and speaking with them about Adnan, as if it might reveal his guilt.

Koenig is translating this story, playing the hero. Adnan Syed’s attorney, Rabia Chaudry, credits Serial for his second chance, saying “the post-conviction appeal only happened because of the attention.” This awareness is the purpose of journalism: to amplify the voices of the conversations we are having, but this seems like a conversation that Koenig has never had before. That’s where this deliberate storyline really loses its strength, and other voices in this story, besides Adnan’s, get lost in generalizations and otherness.

The lead witness, Jay, is African American, and constantly portrayed as suspicious and mysterious. After Serial ended, Jay decided to do an exclusive interview with Natasha Vargas-Cooper over at The Intercept – where he explained that “I don’t want to talk about this for entertainment purposes.” Koenig had taken a traumatic event and turned it into a sensation – taking the story from him and making him feel “demonized.” Koenig knew Jay’s feelings about the case – but to prove her diligence, she shows up at his house. She’s not the first to just show up at Jay’s house, either. The obsession of Serial has caused Jay’s personal documents, photos, and even his address to be leaked online where other self-appointed “investigators” would come to check out Jay and his family. It is through this that Koenig missed realizing that her privilege gave her control of this narrative, full control of her privacy and reputation while she manipulated the reputations of others in the story that she told.

Many of these instances are visible throughout Serial, and we cannot ignore them. We cannot pretend it’s exemplary of how a story about marginalized communities can be successful. It’s not simply about how Koenig’s privilege distorts her story, but it’s proof of how her privilege exploits others. That’s the point of privilege – it’s something we can’t see in ourselves. We cannot keep shrugging it off that the stories of people of color are being told through a lens of white-privilege.

Leave a Reply