It’s November again and the first thing that comes to mind for most people is Thanksgiving. It’s one of the few times in the year where family, friends, loved ones, and even strangers come together around the dinner table. While we bask in the food we eat and enjoy each other’s company, we must not forget that this holiday has many different meanings.

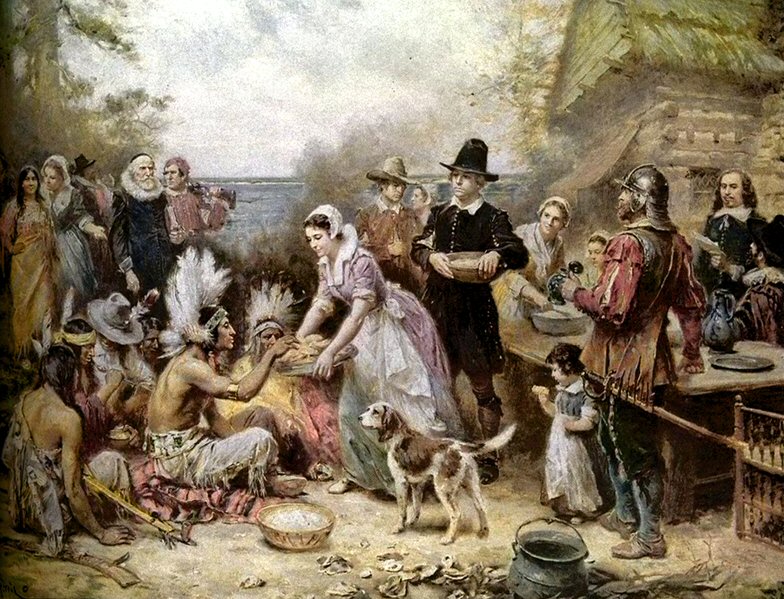

Indigenous Peoples often come to mind during this time of year. But there are a lot of myths and stereotypes that surround Indigenous Peoples and their involvement with Thanksgiving. To truly honor Native American Heritage Month—what I call Indigenous Month—a good place to start would be to deconstruct some of these historical myths and stereotypes. Not only does this create an open and positive dialogue with Indigenous Peoples today, but it will also give some insight to the mixed feelings toward this holiday.

Since that first “historic” meal, the United States of America has subjected Indigenous Peoples to a series of injustices. From the middle of the 18th to the late 19th century, the United States enacted policies of extermination, genocide, removal and relocation. Then, from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, the policies shifted towards assimilation, reformation, and “Americanization.” Then, from the middle 20th century to the present, we’ve faced new challenges such as displacement and disenfranchisement. We currently stand as the most underserved demographic in the United States. This is where and why those mixed feelings toward Thanksgiving for a lot of tribal nations and families, including my own, come from.

Every other year, my family and I go back to my grandmother’s house on the rez in Twin Lakes, N.M., for Thanksgiving. We all help in some way or another: in the kitchen, cleaning up around the house, or going to the store to pick up pumpkin pies. While in the midst of all this preparation, we, like any other family, try our best to get along with each other. In the end, despite our faults and criticisms, we still come to the table and sit down as a family. While we give thanks and cherish certain values that Thanksgiving highlights—family, friends, giving and showing appreciation—we still bear in mind the larger issue of what this holiday tries to conceal.

We don’t give praise or thanks to the pilgrims or naively admire that one point in time when Natives and non-Natives put their differences aside and sat down as “one family.” We don’t forget or forgive the span of over three-hundred years of oppression and injustice that has taken place against Indigenous Peoples. And that’s why it’s not unheard of to see or hear an Indigenous family or community celebrate Thanksgiving…because they do it in their own way, and with their own context.

Seeing as the month of November is Native American Heritage Month—or, again, as I like to call it “Indigenous Month”—this is also a time to inform and educate both the Native and non-Native communities that Thanksgiving carries multiple meanings, some good and others not so good. And what we can do now is have that honest and open dialogue and transparency between Native and non-Native peoples. Because only then can we move forward.

Leave a Reply